The Konkin-Rothbard Divide

TAGLINE. A significant event in the history of libertarianism has received virtually no attention: the ideological schism between iconic figures Samuel E. Konkin III and Murray N. Rothbard.

Samuel E. Konkin III (SEK3) founded Agorism—a social philosophy that seeks to create a voluntary society through the peaceful revolution of counter-economics. He defined “counter-economics” as “the study or practice of all peaceful human action which is forbidden by the State.” In short, it is voluntaryism in both economic and social relations. It is a form of civil disobedience that declines all participation in or with the state; in fact, it attacks participation. Individual by individual, counter-economics spreads throughout society but, even before the strategy becomes a popular trend, individuals who practice it benefit personally.

Driven by SEK3’s amazing energy and focus, Agorism became popular on the West coast of America in the late 20th century, centering in Southern California. It stalled somewhat before the 21st century, partly due to the rise of the Libertarian Party (LP) and the associated popularity of electoral politics. Agorism currently enjoys an impressive resurgence, however.

SEK3 also called himself a “left-libertarian”. The term emerged from SEK3’s experience with the periodical Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought (1965-1968), which was “edited and largely written by Murray N. Rothbard.” (The other two less-active editors were Leonard P. Liggio and H. George Resch.) The periodical’s first editorial “The General Line” explained: “Our title, Left and Right, reflects our concerns in several ways. It reveals our editorial concern with the ideological; and it also highlights our conviction that the present-day categories of ‘left’ and ‘right’ have become misleading and obsolete, and that the doctrine of liberty contains elements corresponding with both contemporary left and right.” Anti-war is an example of a left-wing issue that was compatible with libertarianism; free trade was a right-wing one. When asked what the term “left-libertarian” meant, SEK3 said he was “to the left” of Rothbard, although some of the difference was a matter of emphasis and personality; Rothbard did not embrace the counterculture, while SEK3 reveled in it.

Rothbard was known as “Mr. Libertarian” because of his pioneering and voluminous work that many believe launched modern libertarianism. He merged four world views: Austrian economics, the radicalism of 19th-century individualist anarchism, non-interventionist foreign policy, and the basics of Randian philosophy. Like SEK3, Rothbard created something new under the sun. Unlike SEK3, his creation immediately inspired a generation of libertarian scholars.

Despite some ideological differences, the two men had an affable and productive relationship for many years, albeit with a temporary estrangement occurring during the period Rothbard aligned with Charles Koch whom SEK3 harshly criticized.. They socialized at gatherings, lectured at the same venues, published in each other’s periodicals, and generally spoke well of each other. Then, in 1981, a schism opened. A previously amiable disagreement on electoral politics became a public break. And the movement has been left to wonder what theories, writing, and activism might have emerged if these two icons had continued to cooperate.

A Front Seat on the Side Lines

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, the libertarian movement was much smaller than it is today, and quite a few activists were friendly with both SEK3 and Rothbard. They witnessed the evolution of events that broke the two men apart. I was one of those people. SEK3 was a good friend with whom I frequently lunched or shared an adult beverage; Rothbard was a mentor, with whom I met when he flew in from NYC for conferences or stints of work. I became part of Rothbard’s West coast “circle”—at first because he liked to flirt and then because I became a Rothbardian anarchist.

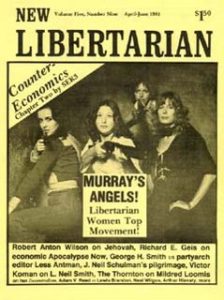

Both men could be prickly, and each exuded extreme confidence in every word they spoke…arguably, with cause. Despite their strong personalities, however, a genuine camaraderie and mutual respect existed. Rothbard contributed to SEK3’s best-known periodical, the New Libertarian (1978-1990), which he called the movement’s foremost “in-reach” magazine. In turn, SEK3 thought so highly of Rothbard that the April/June 1981 issue of New Libertarian featured a cover image of four women clustered together, provocatively pointing guns at the camera. The four of us—me, Janice Allen, Sondra Hendricks, and Maureen Genteman—were trumpeted on the cover as “Murray’s Angels.” To inspire an appropriately mean look on our faces, SEK3 exhorted us to “think of the State!” At the same time the camera snapped, however, a divide loomed. Rothbard was becoming passionately invested in electoral politics, specifically the Libertarian Party (LP).

SEK3 was equally passionate about non-voting. In a rebuttal of the pro-voting stance of the editor of Liberty magazine Bill Bradford, SEK3 laid out the “three distinct positions in This Movement of Ours concerning voting and politics.” A person may “believe that the State can be placated, petitioned, or purchased… and thus one’s ballot (among millions) might be part of that supplication.” A person “feels that dealing with the political system in any way other than rejection of temptation is in error and impure.” And, then, there was the agorist option, the pure choice; “voting is statist…and should be fought. Burn the polls ye sons of freedom!” According to SEK3, “Mr. Libertarian, Murray N. Rothbard, Ph.D., embraced all three” at one time or another.

Rothbard on Electoral Politics

SEK3 referred to “a delicious issue of Perspectives from the early 1960s” in his library. In the periodical’s pages, Rothbard apparently denounced voting and candidates in “pure, anti-political anarchist” fashion. True, Rothbard “had supported Strom Thurmond for President in 1948, but he saw it as a student prank with bite” that was attractive because his fellow students at Columbia University “were divided between Communist-backed Henry Wallace, and the New Deal heir, Harry S. Truman…Rothbard’s Thurmond support was in-your-face New York attitude.” Besides which, he “knew Thurmond could not win electoral votes in New York.”

By 1972, in a February interview with The New Banner: A Fortnightly Libertarian Journal, Rothbard expressed a different view of electoral politics; it was a defense. “The classical-anarchist position is that nobody should vote, because if you vote you are participating in a state apparatus… I don’t think voting is a real problem. I don’t think it’s immoral to vote, in contrast to the anti-voting people.” To Rothbard, voting was defensive. “To me the important thing is, who do you support? Who do you hope will win the election? You can be a non-voter…but on election night who do you hope…they’ll elect…I really don’t agree at all with the non-voting position in that sense, because the non-voter is not only saying we shouldn’t vote: he is also saying that we shouldn’t endorse anybody…I don’t see how anybody could fail to have a preference, because it will affect all of us.”

(Note: Rothbard conflates a preference with an endorsement. Preferring to be shot rather than tortured to death is not an endorsement of being shot nor an admission that voting is defensive. There are other, real defenses. Moreover, Rothbard was well aware of the classical-anarchist non-voting arguments of Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker which were much more sophisticated than the one he presents.)

Despite his defense of voting, Rothbard did not evince enthusiasm when the LP organized in 1971 under David Nolan because he believed the time was not ripe for such a strategy. In an interview entitled “Smashing the State for Fun and Profit Since 1969,” SEK3 observed, “Murray Rothbard and many others refused to take Nolan’s party seriously during the Hospers-Nathan [Presidential-Vice Presidential] campaign. It would have vanished without a trace had Nixon Presidential Elector Roger MacBride not jumped the fence and voted for Hospers instead of Nixon in the Electoral College…Walter Block, who was a rare LP candidate for lower office in New York in 1972, ran his campaign humorously for the State Assembly by putting out bumper stickers calling for ‘Block for Disassembly’.”

Whether it was due to the electoral vote or the energy of the nascent LP, Rothbard was deeply involved by 1975. After all, since student days, he had enjoyed the high-stakes swirl and street fighting of electoral politics; they invigorated him. He attended LP conventions and meetings, wrote position papers, and actively shaped the Party platform. Rothbard was well placed to exert influence. In 1974, he had co-founded the Charles Koch Foundation with the Kansas oil billionaire Charles Koch and LP National Chair (1974-1977) Ed Crane among others; the Foundation later became Cato Institute. In the same period, Rothbard also established an impressive number of advocacy organizations and periodicals.

Rothbard wanted an uncompromisingly libertarian LP. The Libertarian Forum (May-June 1979) announced a new Libertarian Party Radical Caucus (LPRC) in which Rothbard served as a member of the Central Committee—the LPRC’s governing body. The caucus’s goal was “to unify the party around radical and hardcore libertarian programs.”

The purity issue, along with other conflicts, made Rothbard grow increasingly critical of the “Kochtopus”—a term coined by SEK3 in the New Libertarian (February 1978) to signify the pervasive influence of Koch’s money throughout the movement, particularly its institutions and periodicals. The 1979 Libertarian Convention and campaign became a turning point for Rothbard. The nominee for president was lawyer Ed Clark; the nominee for vice president was billionaire David Koch, brother of Charles. Crane, who had managed Clark’s 1978 campaign for California Governor, took a leave of absence from Cato in order to become Communications Director for Clark’s 1980 Presidential run.

The campaign infuriated Rothbard. When a TV interviewer asked Clark to describe libertarianism, for example, he called it “low-tax liberalism.” In 1977, Rothbard had praised the LP National Committee’s strategy resolution, which is widely believed to have been written by him, at least in part. Rothbard declared of the resolution, “The LP now sets itself firmly against all forms of preferential or obligatory gradualism, against the sort of surrender of principle that says we should not cut Tax A by more than X%, or that we should not repeal statist measure B until we can repeal C.” To add insult to injury, Clark’s perceived “sell out” delivered a modest fraction of the votes that had been forecasted.

An open break was inevitable. “The Clark Campaign: Never Again” appeared in the June-Sept.-Dec., 1980, issue of Libertarian Forum. Rothbard exclaimed, “The proper epitaph for the Clark campaign is this: ‘And they didn’t even get the votes.’ Libertarian principle was betrayed, the LP platform ignored and traduced, our message diluted beyond recognition, the media fawned upon—all for the goal of getting ‘millions’…of votes. And they didn’t even do that. All they got for their pains was a measly 1% of the vote. They sold their souls—ours, unfortunately, along with it—for a mess of pottage, and they didn’t even get the pottage.” And, yet, the experience did not make Rothbard reject electoral politics; he doubled down on getting it right.

In turn, Cato fired Rothbard, who claimed his shares of Cato stock were arbitrarily canceled—that is, stolen. Rothbard described the Cato purge of 1981 in the January-April, 1981 issue of Libertarian Forum in an article entitled “It Usually Ends with Ed Crane”; this was a take-off on Jerome Tucille’s popular book It Usually Begins with Ayn Rand. The bitter ideological, strategic, and political conflict became personal as well. Rothbard and the Koch’s cut ties and an obsessive, acrimonious, and public feud with Crane ensued for many years. At this point, Rothbard seemed to lose tolerance for those who disagreed with him on electoral politics.

SEK3 on Electoral Politics

Few people disagreed more fundamentally than SEK3, who saw voting as an act to deride and oppose. He was aggressive in doing so. SEK3 and his anarcho circle had a reputation for interrupting or heckling LP speakers at Supper Clubs, for example.

In his defense, SEK3 had a positive measure to substitute for electoral politics: Agorism. In his pivotal work, the New Libertarian Manifesto (1980), he describes the “best form of organization” with which to start an agorist movement. It “is a Libertarian Alliance in which you steer the members from political activity…and focus on education, publicity, recruitment and perhaps some anti-political campaigning (i.e. ‘Vote For Nobody’, ‘None of the Above’, ‘Boycott the Ballot’, ‘Don’t Vote, It Only Encourages Them!’ etc.) to publicize the libertarian alternative.”

SEK3’s book criticizes Rothbard, but the overall tone is friendly. In fact, the New Libertarian Manifesto opens with an endorsement by Rothbard. “Konkin’s writings are to be welcomed. Because we need a lot more polycentrism in the movement. Because he shakes up Partyarchs who tend to fall into unthinking complacency. And especially because he cares deeply about liberty and can read-and-write, qualities which seem to be going out of style in the libertarian movement.” On the other hand, the book adamantly opposes not only the Partyarchs but also Rothbard on voting.

Rothbard’s review of the New Libertarian Manifesto states, “Konkin is trying to cope with the challenge I laid down years ago to the antiparty libertarians: OK, what is your strategy for the victory of liberty?” The New Libertarian Manifesto does seem to be SEK3’s answer. “While no one can predict the sequence of steps which will unerringly achieve a free society for free-willed individuals,” he wrote, “one can eliminate in one slash all those which will not advance Liberty, and applying the principles of the Market unwaveringly will map out a terrain to travel.” First and foremost, the road that led away from was electoral politics which SEK3 calls “Our Enemy, The State.”

The enemy attacks freedom in three basic ways.

- Corrupt intellectuals advocated anti-principles, such as “Minarchy, Collaborationism,” and “accepting State office to ‘improve’ Statism! …Worst of all is Partyarchy, the anti-concept of pursuing libertarian ends through statist means, especially political parties.”

- The LP was unleashed like an invading army on “fledgling Libertarians”.

- “One of the ten richest capitalists” in America (Charles Koch) bought up and dominated the institutions of the movement.

SEK3 then launches into the meat of the book: “Agorism: Our Goal.” He discusses what a free society looks like, how rights can be defended, and how justice is best delivered to aggressors. (Note: contents of the book that do not address electoral politics are lightly touched upon, if discussed at all.)

The next section is “Counter-Economics: Our Means.” How do we get there from here? The answer is counter-economics—the “actual practice of human actions that evade, avoid and defy the State.” Counter-economics is no mean feat because “nearly every aspect of human action has statist legislation prohibiting, regulating or controlling it. These laws are so numerous that [the] ‘Libertarian’ Party which prevented any new legislation and briskly repealed ten or twenty laws a session would not have significantly repealed the State (let alone the mechanism itself!) for a millennium!…Thus an ‘L’P would perpetuate statism. In addition, an ‘L’P would preserve the ill-gotten gain of the ruling class and maintain the State’s enforcement and execution.”

Since “ignorance of economics” is the main reason black market societies and counter-economics fail, agorists need to educate others, especially by example. “Note well,” SEK3 warns, “libertarian activists who are not themselves full practicing counter-economists are unlikely to be convincing. ‘Libertarian’ political candidates undercut everything they say (of value) by what they are doing; some candidates have even held jobs in taxing bureaus and defense departments!” Such people exemplify statism, not freedom.

The “Revolution: Our Strategy” section spells out the New Libertarian that is embodied in the New Libertarian Alliance. “The organization of NLA…is simple and should avoid turning into a political organ or even an authoritarian organization…The first New Libertarian Alliance was formed…by this author in 1974 from recruits from a raid on the ‘L’P, from other movement activists, and a few counter-economists.”

There are four stages of evolution for a society to become agorist.

- Phase 0: Zero-Density Agorist Society during which those engaged in a political activity are steered toward Agorism by counter-economists.

- Phase 1: Low-Density Agorist Society. “The strategy…is to combat anti-principles which strengthen the State and dissipate anarchist energy uselessly.” This is a stage at which electoral politics, and especially the LP, are to be weakened by attacks.

- Phase 2: Mid-Density, Small Condensation Agorist Society when “the first ‘ghettos’ or districts of agorists to appear and count on the sympathy of the rest of society to restrain the State from a mass attack.” SEK3’s anarcho-village in Long Beach, California is the archetypal “district”.

- Phase 3: High-Density, Large Condensation, Agorist Society when the situation approaches revolution.

The section labeled “Action! Our Tactics” claims that Southern California was in Phase 2 and the time was ripe to siphon off people from the LP. “Internally, the ‘Libertarian’ Party has reached a crisis with the 1980 American Presidential election. The premature unmasking of the statism inherent in partyarchy by Crane-Clark’s blatant opportunism has managed to generate not only Left opposition but Right and Center opposition. Major defections mount daily. The failure of some reformist element to oust the Kochtopus by the Denver Convention (August 1981) …would set the U.S.L.P. back dramatically and generate thousands of disillusioned recruits for the MLL [Movement of the Libertarian Left] and anti-party educational and counter-economic activities.”

SEK3 contrasts the libertarian Right with the agorist radical Left. Many of the Right’s principles were actually anti-principles, such as gradualism and minarchism. Reason magazine is offered as an example. Meanwhile, Murray Rothbard and his following occupy the Center, which is “organized in the LP ‘Radical’ Caucus, which supports Clark ‘critically’.” In a footnote, SEK3 refers to Rothbard and “others informing this writer of their imminent defection should more ‘selling-out’ occur.” (I am unaware of such an imminent defection, although I was in good contact with Rothbard at the time.) A special note in the second edition of the New Libertarian Manifesto (1982) reads, “A steady trickle of LP defectors have added to the ranks of MLL month by month since then [the first edition]. At least one new Left Libertarian group, the Voluntaryists, have arisen to compete for the ex-partyarchs. And Murray Rothbard is organizing, at this time, a last-ditch showdown for control of the LP with the Kochtopus remnant at the LP presidential nominating convention to be held in September 1983 in New York City.”

Rothbard Responds

The first edition of New Libertarian Manifesto is dated October 1980; Rothbard’s reply is dated November 10, 1980. His critique was submitted to Strategy of the New Libertarian Alliance, in which it appeared on May Day 1981. Libertarian Vanguard, August–September 1981, reprinted Rothbard’s response under the title “The Anti-Party Mentality”. (Again, only the aspects of the review addressed are ones concerning electoral politics.)

The critique is organized into four parts:

- The Konkinian Alternative

- The Problem of Organization

- The Problem of the “Kochtopus”

- The Problem of the Libertarian Party

The Konkinian Alternative: Rothbard maintains that the economic arrangement presented by SEK3 is not how the free market works, and this is the New Libertarian Manifesto’s “fatal flaw”. Rothbard zeros in upon the practice of “working for wages” that SEK3 verges on rejecting outright as a holdover from feudalism; Rothbard considers it to be an integral part of a market economy. Rothbard ties the issue to electoral politics through “tax rebellion, which presumably serves as part of the categoric strategy. For once again, it is far easier for someone who doesn’t earn a wage to escape the reporting of his income. It is almost impossible for wage earners, whose taxes are of course deducted off the top by the infamous withholding tax … Konkin’s airy dismissal of taxation as being in some sense voluntary again ignores the plight of the wage earner.”

There is only “one way to eliminate the monstrous withholding tax,” Rothbard contends. “Dare I speak its name? It is political action.”

The Problem of Organization: this focuses on SEK3’s critique of the modern movement. Rothbard concludes, “He wants only individual alliances, and not organizations at all. First, there is nothing either libertarian or unmarked about a voluntary organization, whether joint stock or any other…So organizations create problems; so what? So does life itself, or friendships, romantic relationships, or whatever.” Given that the organization overwhelmingly criticized by SEK3 was the LP, this section of Rothbard’s response can be seen as a direct defense. Although the LP is certainly a voluntary organization in terms of membership—a statement with which SEK3 would have agreed—the question under scrutiny is whether the LP aims at using force in the form of law and government against others.

The Problem of the “Kochtopus”: Rothbard denies the existence of a “Koch monopoly” problem and advises SEK3 to fall back on “Austrian economics” which denies the possibility of a free-market monopoly existing, except through the satisfaction of consumers.

The Problem of the Libertarian Party: “We turn to Konkin’s bete noire, the Libertarian Party,” Rothbard declares. He asks two important questions that need to be resolved about the LP:

“1. is it evil per se, and

- assuming that it isn’t, is it a legitimate or even necessary strategy for libertarians to adopt?”

Rothbard assumes “for the moment” that the LP and “other forms of political action”, such as lobbying, “are not evil per se.” If this assumption is correct, then “all of Konkin’s running arguments about the LP’s hierarchical nature, its power struggles, faction fighting, etc. are no more than the problems inherent in all organizations.” As for the second question, since only a political party can repeal laws, the LP “is vital if not necessary to repealing statism.”

The review’s conclusion is friendly enough. “Konkin’s writings are to be welcomed” because the movement needs polycentrism and because “he shakes up ‘Partyarchs’.” Nevertheless, Rothbard’s sole footnote takes exception to a criticism lodged against him by SEK3. It was that Koch bought “Murray Rothbard and his Libertarian Forum.” Rothbard pointed comments, “One of his criticisms (NLM, page 5) is untrue as well as insulting. Neither I nor the Libertarian Forum was ever in any sense ‘bought’ or ‘bought out’ by Charles Koch. The Libertarian Forum has never had a penny from outside sources: since its inception, it has been entirely self-financing.”

The Last Word Goes to SEK3

Of course, SEK3 responded. “Rothbard, alas, is decidedly short of actual weapons. His accusation of a fatal flaw—seemingly the fatal flaw [wage-earning]—of agorism is so irrelevant to the basis of agorism that it is barely mentioned en passant and in a footnote of the New Libertarian Movement (footnote * p. 21).”

On the central issue of electoral politics and the LP, SEK3 observes, “Rothbard says he will ‘assume for the moment that a libertarian political party…is not evil per se.’ I wonder how open he would be to assuming the State is not evil per se and then continuing the discussion of some legislation, let us see where it leads him. It seems to lead to the wonder of repeal of laws.”

The closest SEK3 comes to bristling is in reaction to a concluding comment in Rothbard’s critique. Rothbard had stated, “Konkin is what used to be called a ‘wrecker’; let some institution or organization seem to be doing good work for liberty somewhere, and Sam Konkin is sure to be in there with a moral attack.” SEK3 counters, “Rothbard’s characterizing me as a ‘wrecker’ is truly surprising to me considering all the libertarian organizations and publications I have built up and supported—more than anyone else save Dr. Rothbard himself…The only things I’ve wrecked are the wreckers of our once party-free movement.”

The rebuttal concludes with a call for Revolutionary Dialogue between the two men. “If the New Libertarians and the Rothbardian Centrists must devote some time to our differences (“engage in Revolutionary Dialogue”), let it be devoted first to understanding each other…and then resolving the differences. Ah, then let the State and its power elite quake!”

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the good will did not last long enough for a detente. Or, perhaps, the principles involved were so antithetical that no resolution was possible, in much the same manner that pro-choice and pro-life libertarians are doomed to conflict. Rothbard became increasingly critical of anti-electoral voices, including one that was highlighted by SEK3: the modern Voluntaryist movement. Established in 1982 by Carl Watner, George H. Smith, and me, the Voluntaryist organization and newsletter argued against the legitimacy of the state—including voting and electoral politics—and for the myriad of peaceful strategies through which to achieve freedom. By 1982, however, Rothbard’s response to critics on this topic was far from measured, and it led to more permanent schisms. But this is another story.

Rothbard had a principle of human behavior: the 10% rule. Reasonable libertarians who were 90% sound in their beliefs often had a 10% deviation that they spent 90% of their time justifying. This was a self-fulfilling principle in Rothbard’s case regarding his support of the LP and electoral politics.